Voices & Images: Swil Kanim

In Conversation: Will Wilson, with support provided by Art Bridges, comes to the Albany Museum of Art as part of the AMA’s commitment to sharing stories and perspectives from all Americans. Through the artistic manipulation of light and chemistry, this exhibition connects two photographers from different eras, both dedicated to documenting and preserving identities but with vastly different approaches. It brings their works into conversation.

At the turn of the 20th century, American photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868-1952) embarked on a journey to produce a series of portfolios documenting Native Americans and their ways of life. The results, published as The North American Indian (1907-1930), were decidedly romantic while being received as reality. A common misbelief of this time was that Native American cultures were vanishing, and Curtis dedicated more than 30 years of his life to documenting over 75 Indigenous North American groups.

However important his work was to preserve a historical record of many Indigenous peoples, in actuality, Curtis reduced his subjects to archetypes rather than allowing for personal agency. He would often provide props, suggest sitters wear their finest clothing or ceremonial attire despite posing for everyday tasks, and worked diligently to ensure no examples of modern life or European influence appeared in his constructed scenes.

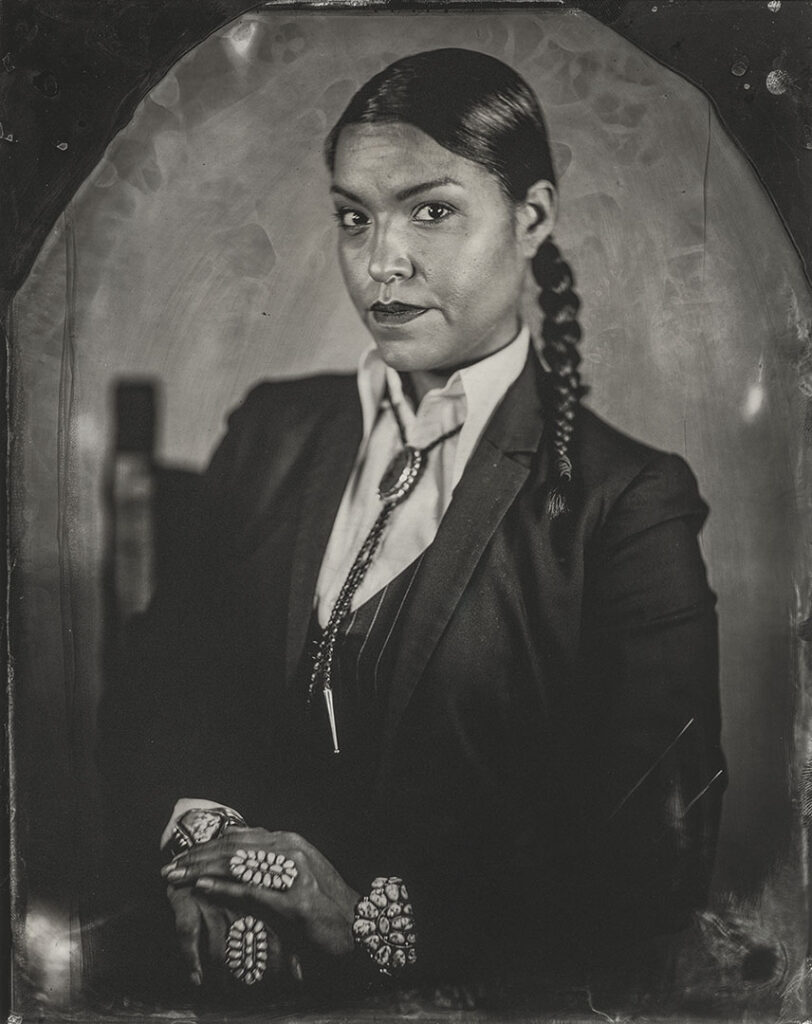

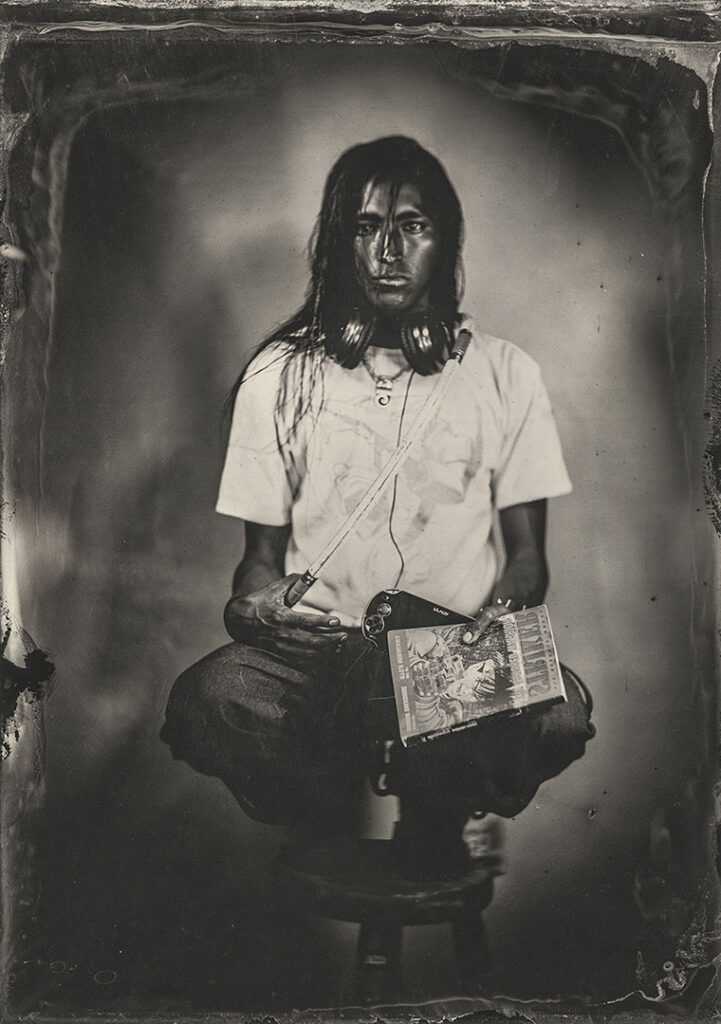

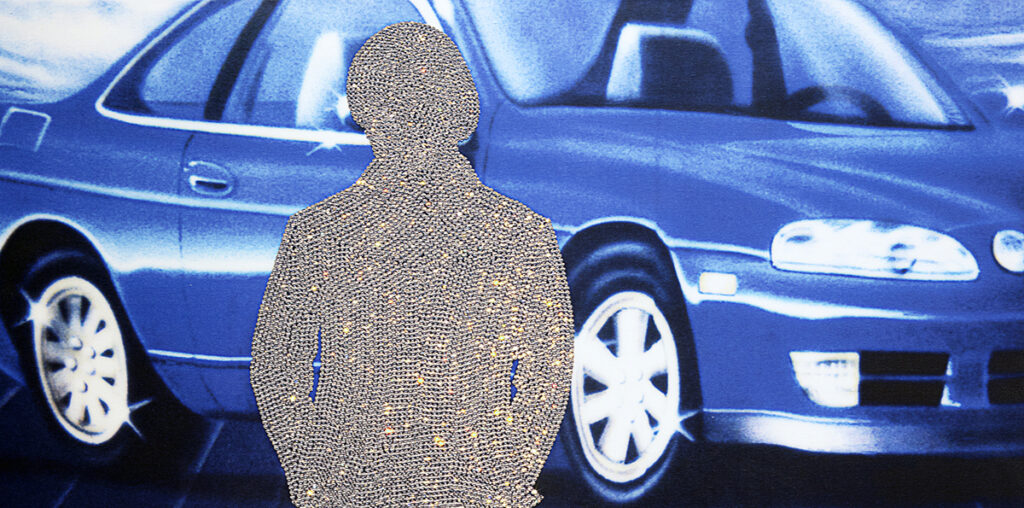

Contemporary Diné (Navajo, b. 1969) photographer Will Wilson’s ongoing Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) project is dedicated to creating a 21st-century vision of Native North America by challenging the long-standing acceptance of Curtis’ documentative photos from The North American Indian compendium. For CIPX, Wilson employs a wet-plate collodion photographic technique, based on the 19th-century method that involves exposing and then developing a plate that has been coated in light-sensitive chemicals. Through his work, Wilson explores identity, the photographic medium as both art and science, and community. Wilson’s use of the word “exchange” in his project is a very intentional choice. He collaborates with his sitters, who determine the pose, clothing, props, and how they are presented. As a gesture of reciprocity, Wilson gives the sitters the original photograph, while retaining the right to print and use scans for artistic purposes. He does not simply capture their likeness but has meaningful encounters with his sitters that go beyond the tintype.

In the 1880s, the U.S. government actively suppressed Native American religious practices by enforcing the “Code of Indian Offenses,” which banned traditional ceremonies, rituals, and beliefs, with the goal of cultural assimilation through policies that continued until at least 1934. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced relocation of tribes from east of the Mississippi River to lands in the west. Curtis was born about 38 years later and was raised with knowledge of these events. During Curtis’ production of The North American Indian, he was asking Indigenous groups to skirt the law and perform ceremonies and rites that were essentially banned by the United States government. His fabricated scenes notwithstanding, Edward Curtis made strides in preserving the memory of Indigenous culture, but did so through controversial means, which should not be separated from the result of his work.

In award-winning filmmaker Anne Makepeace’s own words from her book and subsequent documentary, Edward S. Curtis, Coming to Light, she shares what she learned during her research regarding her own experiences, which were, at times, quite similar to Curtis’ while attempting to photograph and record Indigenous ceremonies:

“Since the time the first photographers went West, the idea of photographing ceremonies has been extremely controversial. Many Indian people feel that the camera is an invasion of privacy. Some also believe the photographs negate the effects of their prayers. … When the Navajo or the Kwakiutl had donned masks to perform dances for [Curtis’] camera, or when the Sioux and Crow had reenacted battle scenes on horseback, they were doing so to contribute to a photographic record that would be of value to their children and grandchildren. Most Indian people today refer to their departed family members as relatives, not as ancestors. The spirits of the dead are still with them, and Curtis’s photographs are the gifts of the departed relatives to the present generation.”

Likewise, Wilson does the same, to capture and keep memory alive. Through his Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, Wilson firmly asserts his identity and his sitters’ identities as their own, not constructed versions of a romanticized ideal. Furthermore, Wilson brings his photographs into the 21st century by utilizing Augmented Reality (AR) technology to make some of his tintypes “talk.” By downloading this free app, developed by Wilson himself, “Talking Tintypes,” visitors can experience a new depth to these tintypes and feel like they, too, are a part of the conversation.

Art That Speaks You

Talking Tintypes bring Will Wilson’s photographs to life in In Conversation: Will Wilson.