One of the first exhibitions of African art in the United States took place at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York in 1923. Primitive Negro Art, Chiefly From the Belgian Congo was the presentation of a body of work from the Democratic Republic of the Congo collected by the curator of the exhibition, Stewart Cullen. This early exhibition, in its written documentation and installation, launched a world of exhibitions and scholarship that would alter drastically throughout its history.

For context, the Brooklyn Museum opened about 100 years before Cullen’s exhibition, and the institution did not begin to build its permanent collection until the early 1900s. Cullen’s artworks were among the first to build the museum’s collection, which now contains over 4,000 pieces.

In an essay that followed the exhibition, Cullen provided further context for the pieces displayed and the overall intention of the show. It’s important to note that at the time of the exhibition, terms like “primitive” were in constant use. As scholarship and research on African communities furthered, this term was deemed inaccurate and inappropriate.

In addition to the early use of “primitive” and “primitivism,” there was a romanticization of the noble savage placed on these African communities and their art-making.

Cullen noted in this essay that the pieces on display were to be seen in the context of art, but there was a certain exoticism ascribed to the artworks. He stated that “the Bushongo have a high artistic sense, and are most advanced in the arts,” calling these creatives amateurs rather than artists in their own right.

While this exhibition marked the beginning of an educational and curatorial focus and practice that is now over 100 years old, there have been many key mobilizing changes.

In Albany, the presentation of African art has long been at the center of the mission of the Albany Museum of Art. The primary motivator was Albany native Stella E. Davis. Employed by the U.S. Government, she spent a large part of the early and mid-20th century on the African continent. Davis later donated a large part of her collection to the museum, which presented the first iteration of From African Hands around 1971, when it was still the Southwest Georgia Art Association. The exhibition was likely on view several other times, including 1973 and the 1980s, when the AMA moved to its current home at 311 Meadowlark Drive.

Groundbreaking for its time, From African Hands was curated by community members who valued education and exposure to resources that were otherwise unavailable.

A catalog produced for the 1973 exhibition includes a short essay in which Davis states: “Africa is still a continent of craftsmen and artists, a world of hand-made artifacts, a reservoir of ritual objects. While in Africa, I found objects of unexpected beauty in the simplest village along the narrowest roadway.” There is a clear regard, respect, and deep value of these works, but also a slight oversight. There is still a struggle for works coming from the African continent to be seen as fine art. Artists are referred to as craftsmen, and the presumption is that there is a presence of talent and skill in their art making, in spite of Western or traditional fine art ideals.

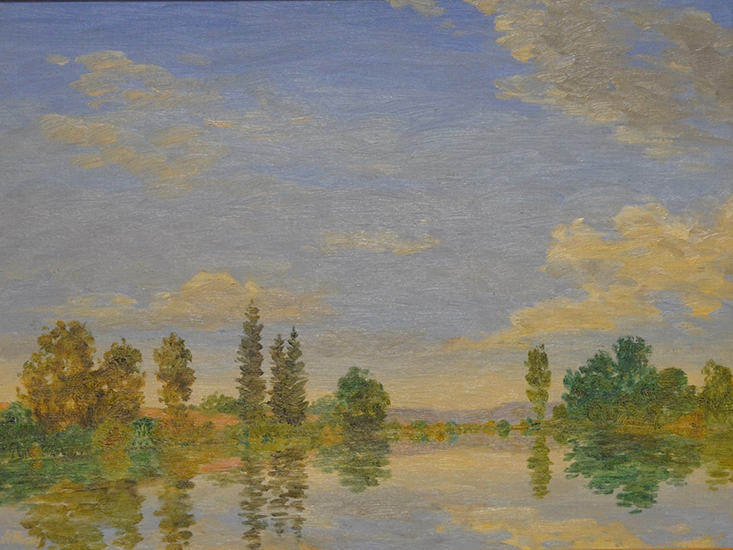

The 1973 catalog also touches on an interesting dynamic within African art and Western art history. Concurrent with African art struggling to find its place in the fine art canon, Modernism was taking influence from African art while disregarding the spiritual and ritual symbolism in these pieces. Picasso, Kandinsky, and others took inspiration from this genre of art that was outside of a rapidly expanding art world.

What are the changes that have been made just 50 years after the 1973 presentation of From African Hands and over 100 years after Primitive Negro Art, Chiefly from the Belgian Congo? Primarily, there have been drastic changes in the ways African art is discussed, especially regarding works that have a specific stylization or a spiritually charged nature. The gap has been bridged between the traditional art historical canon and African art and artists that are now intentionally placed into the category of fine art.

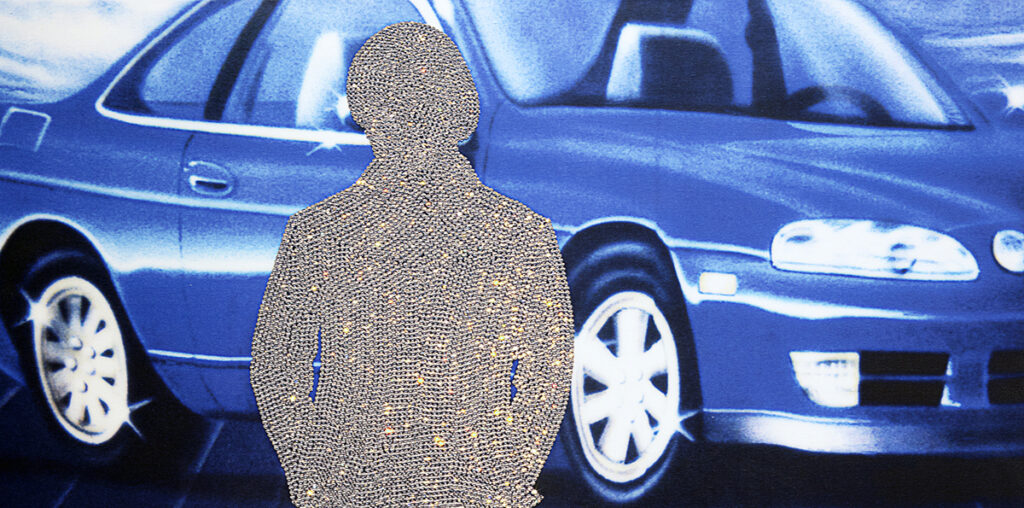

In Echoes of the Past, there is a revisiting and reimagination of historic exhibitions such as the museum’s own From African Hands. By exhibiting these pieces on a large scale—encompassing the Haley, East, and Hodges galleries—this African art survey exhibition aims to highlight and acknowledge the needed changes that have happened in the art historical and cultural research fields.

Through the display of the AMA’s Sub-Saharan African Collection, with additional works on loan from partnering institutions—the North Carolina Museum of Art, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, and the Savannah African Art Museum—Echoes of the Past invites visitors to experience and sit with the deep cultural and historical importance of this show.

Echoes of the Past is the first large-scale survey exhibition of African art to take place at the AMA in nearly half a century. This show is not only a cause for celebration as the museum acknowledges the legacy and longevity of these works within its collection, but also because of the essential and timely subject matter. African art has and will always be a facet within fine art.

With pieces hailing from many different communities and cultures, the visual art from this continent invites moments of reflection on topics of ritual, religion, tradition, community, and remembrance.